How to Use Force-Field Analysis with Diagrams and an Action Plan to Strengthen Driving Forces

Organisational change can feel like pushing a boulder uphill—every gain comes with resistance. Whether you’re rolling out a new system, changing structures, or shifting culture, even the most necessary initiatives can stall if people and processes push back. That’s where force-field analysis becomes a powerful tool: it gives leaders a structured way to understand what’s helping or hindering progress—and what to do about it.

In this article, we’ll walk through how to use force-field diagrams to map out these pressures and develop a practical, actionable plan to increase the driving forces that support your change initiative. Whether you’re a change manager, consultant, team lead or senior leader, this approach will give you clarity and control over the forces shaping your outcomes.

What is Force-Field Analysis?

Force-field analysis was developed by social psychologist Kurt Lewin in the 1940s as a framework to understand the factors that influence change in social situations. At its core, the method identifies and analyses the forces that either support or resist a particular change.

These forces are categorised as:

- Driving Forces – factors that push for change (e.g. competitive pressure, leadership support, innovation drivers)

- Restraining Forces – factors that resist change (e.g. fear of job loss, lack of training, outdated systems)

When the driving forces outweigh the restraining ones, change is more likely to occur. The aim of force-field analysis is not just to identify these forces but to act on them—strengthening the drivers and reducing the blockers.

Why Use Force-Field Analysis?

Force-field analysis is particularly useful because it:

- Brings clarity to complex change dynamics

- Surfaces hidden resistances and unstated support

- Encourages participatory planning and stakeholder engagement

- Creates a practical roadmap for increasing momentum

- Helps avoid superficial fixes by targeting root influences

Let’s dive into how to use it effectively.

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Use Force-Field Analysis in Practice

Step 1: Define the Change You Want to Achieve

Begin by clearly articulating the proposed change. The more specific you can be, the more effective your analysis will be.

Example:

“Implement a new digital project management system across the delivery team by Q3.”

Write this in the centre of your diagram or whiteboard—it becomes the reference point for the forces you identify.

Step 2: Identify Driving and Restraining Forces

Next, brainstorm the forces pushing for and against the change. Bring your team or stakeholders into the conversation to ensure you capture diverse perspectives. You’re aiming for a comprehensive list—everything from cultural attitudes to financial pressures.

Driving Forces Might Include:

- Leadership support and mandate

- Frustration with current systems

- Availability of funding

- Competitive pressure

- Efficiency gains

Restraining Forces Might Include:

- Staff resistance or fear

- Lack of time for training

- Technical issues or integration concerns

- Union objections

- Previous failed initiatives

Use a force-field diagram to visualise this: draw a horizontal bar representing the current state, with arrows pointing towards the desired state from both directions. Driving forces go on one side, restraining forces on the other.

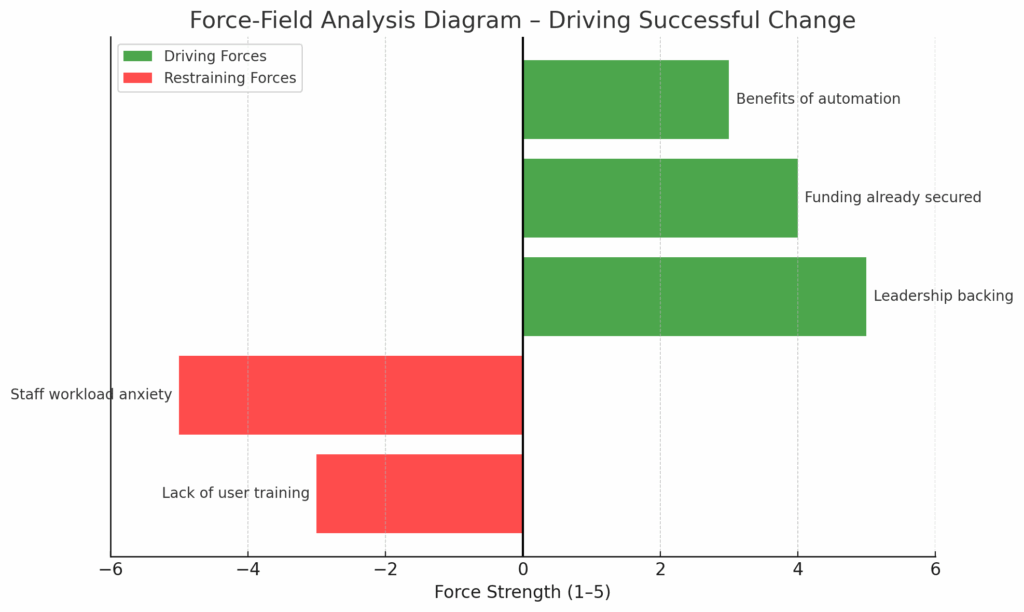

Step 3: Score Each Force by Strength

Not all forces are equal—some may have a stronger impact on the outcome. Use a simple scoring system (e.g. 1 to 5) to assess the strength of each force.

Then redraw your diagram to reflect the scores, with longer arrows representing stronger forces. This helps you visualise which factors need the most attention and which could be leveraged for quick wins.

| Force | Type | Score (1–5) |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership backing | Driving | 5 |

| Funding already secured | Driving | 4 |

| Staff workload anxiety | Restraining | 5 |

| Lack of user training | Restraining | 3 |

| Benefits of automation | Driving | 3 |

This will highlight where action can have the biggest effect.

Step 4: Analyse and Interpret the Field

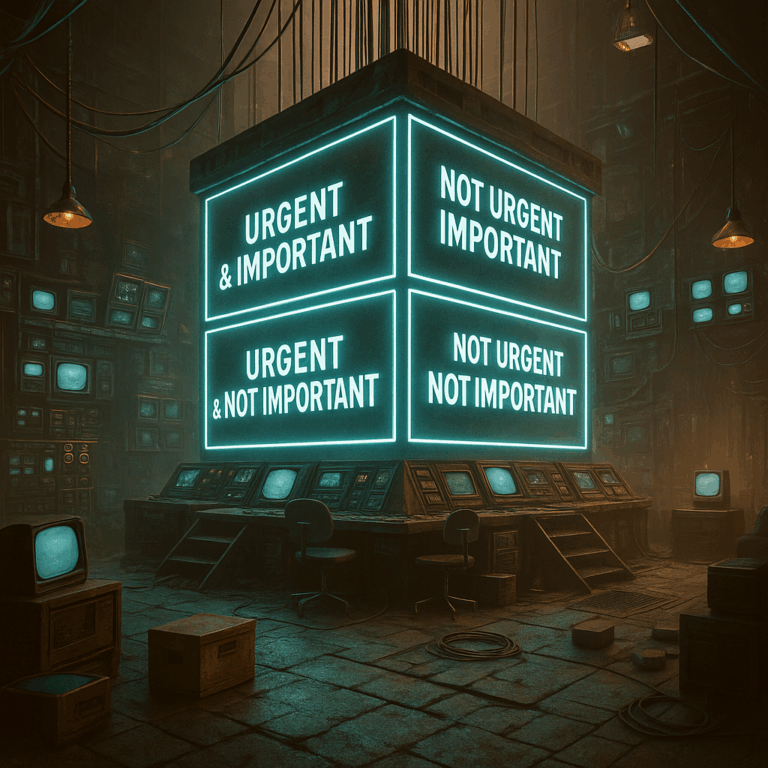

With your forces mapped and scored, you now have a visual representation of the change landscape. Ask:

- Are restraining forces overpowering? You may need to delay or redesign the initiative.

- Are there hidden driving forces you can unlock? These could be early adopters or external influencers.

- Which restraining forces are most addressable? Can they be turned into driving forces?

Step 5: Build an Action Plan to Strengthen Driving Forces

Now we come to the heart of this approach—turning insight into action. Many teams make the mistake of focusing only on reducing resistance. But an equally powerful strategy is to strengthen the driving forces so they overcome resistance.

Use this checklist to guide your action planning:

– Identify Leverage Points Among Drivers

Look at your top-scoring driving forces. Ask:

- Can you amplify their impact?

- Can they be communicated more widely?

- Can they be made more visible?

Example Actions:

- Publicly endorse the change through senior leadership messages

- Share real success stories from pilot teams

- Incentivise participation through recognition or rewards

– Recruit and Equip Change Champions

Early adopters and influencers can become accelerators for change. Recruit them to:

- Model new behaviours

- Act as peer coaches or trainers

- Provide feedback from the ground

– Tie Change to Organisational Goals

Link the initiative to broader business or mission goals so people see relevance and urgency.

For example:

“This system upgrade directly supports our goal of reducing delivery lead times by 25%.”

Step 6: Plan to Reduce or Reframe Restraining Forces

While increasing drivers is powerful, some resistors still need attention. You don’t always have to eliminate them—sometimes you can reframe them or manage them in a way that reduces their impact.

Examples:

- Fear of automation → Provide reassurances about job security, upskilling opportunities

- Previous failed initiatives → Emphasise what’s different this time, and how lessons have been learned

- Lack of time → Offer flexible training or protected time windows

Tactics Might Include:

- Communications and engagement sessions

- Training and support plans

- Early feedback loops and pilots

- Revisiting timelines or scope

Step 7: Monitor and Adapt Over Time

Change is not linear. Monitor the strength of forces over time. Your force-field diagram is not a one-time activity—it should evolve as the initiative progresses.

- Reassess monthly or at key milestones

- Update force scores based on feedback and results

- Add new forces as they emerge

- Use the diagram in regular check-ins and retrospectives

Practical Template: Build Your Own Force-Field Diagram

Here’s a simple template to use in workshops or team planning:

- Define the change clearly at the top

- Create two columns underneath: Driving Forces and Restraining Forces

- List each force and assign it a strength (1–5)

- Use arrows of different lengths to visualise strength

- Discuss potential actions to:

- Strengthen driving forces

- Reduce or reframe restraining forces

- Convert those into a prioritised action plan

This can be done using sticky notes on a wall, a shared digital whiteboard (e.g. Miro, MURAL), or using a spreadsheet template for tracking over time.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Skipping the scoring step: Without weighting the forces, you may spend time on low-impact activities.

- Over-focusing on resistance: Reducing resistance is important, but increasing support is often more effective.

- Using it once and forgetting it: The best results come when force-field analysis is used as a living tool.

- Failing to act on insights: A diagram alone won’t create change—turn it into a plan with owners, dates, and metrics.

When to Use Force-Field Analysis

Force-field analysis is particularly valuable in:

- Strategic planning workshops

- Change readiness assessments

- Risk reviews

- Stakeholder engagement sessions

- Post-mortems or retrospectives

Use it early to shape strategy, or later to unblock stalled efforts.

Final Thoughts: Clarity Before Action

Driving change without understanding the forces at play is like sailing without checking the wind. Force-field analysis gives you that wind map—revealing where to trim sails, add power, or change tack.

By visualising the pressures acting on your change, involving others in the analysis, and crafting a targeted action plan to strengthen driving forces, you’ll turn passive support into active momentum—and resistance into manageable friction.

So next time you’re leading a change initiative, don’t just push harder. Map the forces. Change the field. Drive success.