1. Promises in the Boardroom

The applause in the London headquarters boardroom could be heard down the corridor.

The Chief Executive of GlobalAid International — a humanitarian NGO working across 14 countries — had just announced the launch of Project Beacon, an ambitious digital transformation initiative designed to unify field operations, donor reporting, and beneficiary support onto a single platform.

“Three continents, one system,” she declared.

“A unified digital backbone for our mission.”

Slides glittered with icons: cloud infrastructure, mobile apps, analytics dashboards.

Everyone nodded. Everyone smiled.

At the far end of the table, Samuel Osei — the East Africa Regional Delivery Lead — clapped politely. He’d flown in from Nairobi for this two-day strategy summit. But he felt a small knot forming behind his ribs.

The plan looked elegant on slides.

But he’d spent ten years working between HQ and field teams.

He knew the real challenge wasn’t technology.

It was the hand-offs.

Whenever HQ built something “for the field,” the hand-over always fractured. Assumptions clashed. Decisions bottlenecked. Local context was lost. And by the time someone realised, money was spent, trust was strained, and nobody agreed who was accountable.

Still — Sam hoped this time would be different.

He was wrong.

2. A Smooth Start… Too Smooth

Back in Nairobi, momentum surged.

The HQ Digital Team held weekly calls. They shared Figma designs, user stories, sprint demos. Everything was polished and professional.

Status remained green for months.

But Sam noticed something troubling:

The Nairobi office wasn’t being asked to validate anything. Not the data fields, not the workflow logic, not the local constraints they’d face.

“Where’s the field input?” he asked during a sync call.

A UX designer in London responded brightly, “We’re capturing global needs. You’ll get a chance to review before rollout!”

Before rollout.

That phrase always meant:

“We’ve already built it — please don’t break our momentum with real context.”

Sam pushed:

“What about Wi-Fi reliability in northern Uganda? What about multi-language SMS requirements? What about the different approval pathways between ministries?”

“Good points!” the product manager said.

“We’ll address them in the localisation phase.”

Localisation phase.

Another red flag.

Sam wrote in his notebook:“We’re being treated as recipients, not partners.”

Still, he tried to trust the process.

3. The First Hand-Off

Six months later, HQ announced:

“We’re ready for hand-off to regional implementation!”

A giant 200-page “Deployment Playbook” arrived in Sam’s inbox. It contained:

- a technical architecture

- 114 pages of workflows

- mock-ups for approval

- data migration rules

- training plans

- translation guidelines

The email subject line read:

“Beacon Go-Live Plan — Final. Please adopt.”

Sam stared at the words Please adopt.

Not review, not co-design.

Just adopt.

He opened the workflows.

On page 47, he found a “Beneficiary Support Decision Path.” It assumed every caseworker had:

- uninterrupted connectivity

- a laptop

- authority to approve cash assistance

But in Kenya, Uganda, and South Sudan, 60% of caseworkers worked on mobile devices. And approvals required ministry sign-off — sometimes three layers of it.

The workflow was not just incorrect.

It was impossible.

At the next regional leadership meeting, Sam highlighted the gaps.

A programme manager whispered, “HQ designed this for Switzerland, not Samburu.”

Everyone laughed sadly.

4. The Silent Assumptions

Sam wrote a document titled “Critical Context Risks for Beacon Implementation.”

He sent it to HQ.

No reply.

He sent it again — with “URGENT” in the subject line.

Still silence.

Finally, after three weeks, the CTO replied tersely:

“Your concerns are noted.

Please proceed with implementation as planned.

Deviation introduces risk.”

Sam read the email twice.

His hands shook with frustration.

My concerns ARE the risk, he thought.

He opened a Failure Hackers article he’d bookmarked earlier:

Surface and Test Assumptions.

A line jumped out:

“Projects fail not because teams disagree,

but because they silently assume different worlds.”

Sam realised HQ and regional teams weren’t disagreeing.

They weren’t even speaking the same reality.

So he created a list:

HQ Assumptions

- Approvals follow a universal workflow

- Staff have laptops and stable internet

- Ministries respond within 24 hours

- Beneficiary identity data is consistently reliable

- SMS is optional

- Everyone speaks English

- Risk appetite is uniform across countries

Field Truths

- Approvals vary dramatically by country

- Internet drops daily

- Ministries can take weeks

- Identity data varies widely

- SMS is essential

- Not everyone speaks English

- Risk cultures differ by context

He sent the list to his peer group.

Every country added more examples.

The gap was enormous.

5. The Collapse at Go-Live

Headquarters insisted on going live in Kenya first, calling it the “model country.”

They chose a Monday.

At 09:00 local time, caseworkers logged into the new system.

By 09:12, messages began pouring into the regional WhatsApp group:

- “Page not loading.”

- “Approval button missing.”

- “Beneficiary record overwritten?”

- “App froze — lost everything.”

- “Where is the offline mode?!”

At 09:40, Sam’s phone rang.

It was Achieng’, a veteran programme officer.

“Sam,” she said quietly, “we can’t help people. The system won’t let us progress cases. We are stuck.”

More messages arrived.

A district coordinator wrote: “We have 37 families waiting for assistance. I cannot submit any cases.”

By noon, the entire Kenyan operation had reverted to paper forms.

At 13:15, Sam received a frantic call from London.

“What happened?! The system passed all QA checks!”

Sam replied, “Your QA checks tested the workflows you imagined — not the ones we actually use.”

HQ demanded immediate explanations.

A senior leader said sharply:

“We need names. Where did the failure occur?”

Sam inhaled slowly.

“It didn’t occur at a person,” he said.

“It occurred at a handoff.”

6. The Blame Machine Starts Up

Within 24 hours, a crisis taskforce formed.

Fingers pointed in every direction:

- HQ blamed “improper field adoption.”

- The field blamed “unusable workflows.”

- IT blamed “unexpected local constraints.”

- Donor Relations blamed “poor communication.”

- The CEO blamed “execution gaps.”

But no one could explain why everything had gone wrong simultaneously.

Sam reopened Failure Hackers.

This time:

Mastering Effective Decision-Making.

Several sentences hit hard:

“When decisions lack clarity about who decides,

teams assume permission they do not have —

or wait endlessly for permission they think they need.”

That was exactly what had happened:

- HQ assumed it owned all design decisions.

- Regional teams assumed they were not allowed to challenge.

- Everyone assumed someone else was validating workflows.

- No one owned the connection points.

The project collapsed not at a bug or a server.

But at the decision architecture.

Sam wrote a note to himself:

“The system is not broken.

It is performing exactly as designed:

information flows upward, decisions flow downward,

and assumptions remain unspoken.”

He knew what tool he needed next.

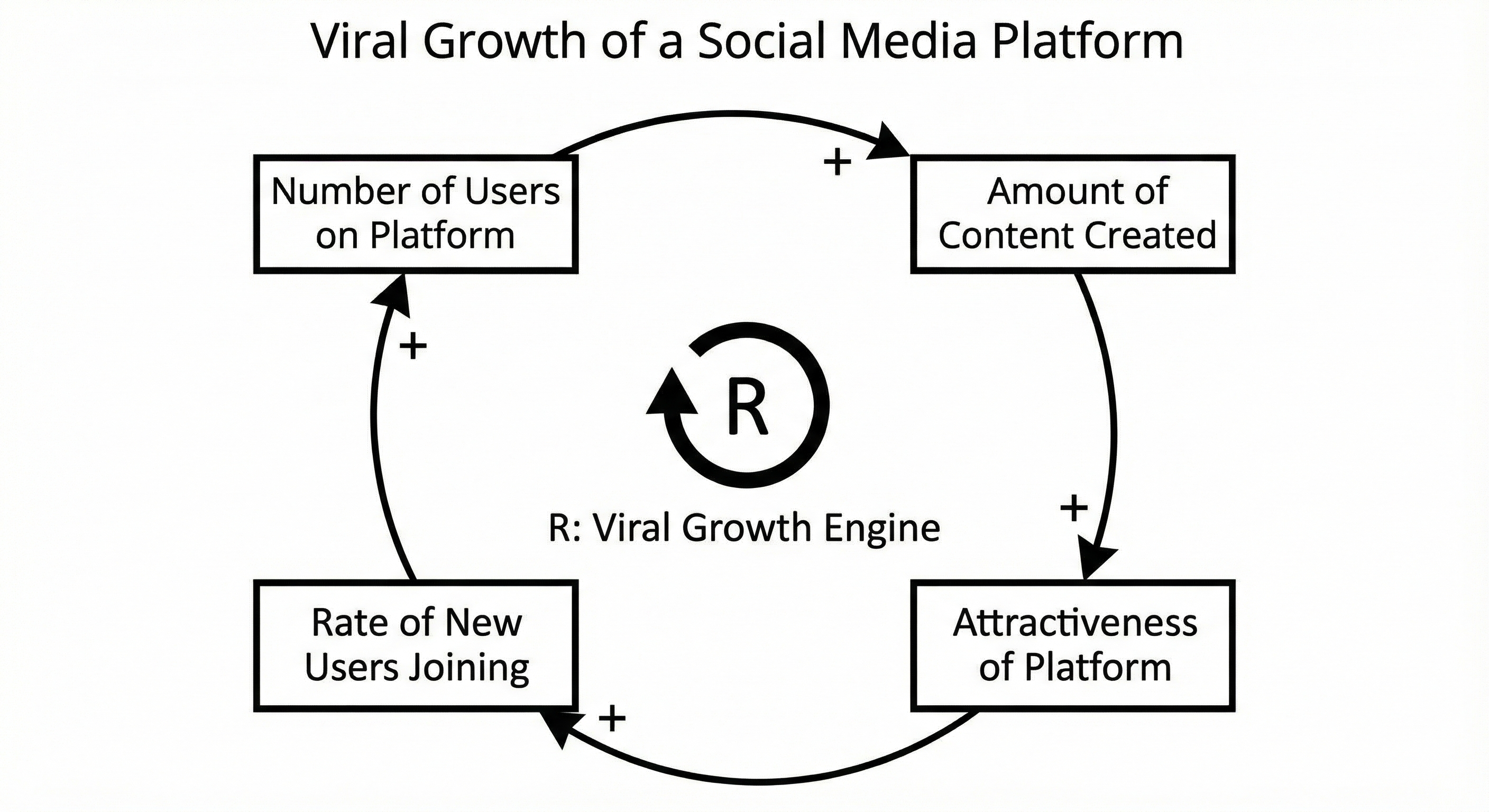

7. Seeing the System

Sam began mapping the entire Beacon project using:

Systems Thinking & Systemic Failure.

He locked himself in a small Nairobi meeting room for a day.

On the whiteboard, he drew:

Reinforcing Loop 1 — Confidence Theatre

HQ pressure → optimistic reporting → green dashboards → reinforced belief project is on track → reduced curiosity → more pressure

Reinforcing Loop 2 — Silence in the Field

HQ control → fear of challenging assumptions → reduced field input → system misaligned with reality → field distrust → HQ imposes more control

Balancing Loop — Crisis Response

System collapses → field switches to paper → HQ alarm → new controls → worsened bottlenecks

By the time he finished, the wall was covered in loops, arrows, and boxes.

His colleague Achieng’ entered and stared.

“Sam… this is us,” she whispered.

“Yes,” he said. “This is why it broke.”

She pointed to the centre of the diagram.

“What’s that circle?”

He circled one phrase:

“Invisible Assumptions at Handoff Points.”

“That,” Sam said, “is the heart of our failure.”

8. The Turning Point

The CEO asked Sam to fly to London urgently.

He arrived for a tense executive review.

The room was packed: CTO, CFO, COO, Digital Director, programme leads.

The CEO opened:

“We need to know what went wrong.

Sam — talk us through your findings.”

He connected his laptop and displayed the Systems Thinking map.

The room fell silent.

Then he walked them step by step through:

- the hidden assumptions

- the lack of decision clarity

- the flawed hand-off architecture

- the local constraints never tested

- the workflow mismatches

- the cultural pressures

- the reinforcing loops that made failure inevitable

He concluded:

“Beacon didn’t collapse because of a bug.

It collapsed because the hand-off between HQ and the field was built on untested assumptions.”

The CTO swallowed hard.

The COO whispered, “Oh God.”

The CEO leaned forward.

“And how do we fix it?”

Sam pulled up a slide titled:

“Rebuilding from Truth: Three Steps.”

9. The Three Steps to Recovery

Step 1: Surface and Test Every Assumption

Sam proposed a facilitated workshop with HQ and field teams together to test assumptions in categories:

- technology

- workflow

- approvals

- language

- bandwidth

- device access

- decision authority

They used methods directly from:

Surface and Test Assumptions.

The outcomes shocked HQ.

Example:

- Assumption (HQ): “Caseworkers approve cash disbursements.”

- Field Reality: “Approvals come from ministry-level officials.”

Or:

- Assumption: “Offline mode is optional.”

- Reality: “Offline mode is essential for 45% of cases.”

Or:

- Assumption: “All country teams follow the global workflow.”

- Reality: “No two countries have the same workflow.”

Step 2: Redesign the Decision Architecture

Using decision-mapping guidance from:

Mastering Effective Decision-Making

Sam redesigned:

- who decides

- who advises

- who must be consulted

- who needs visibility

- where decisions converge

- where they diverge

- how they are communicated

- how they are tested

For the first time, decision-making reflected real power and real context.

Step 3: Co-Design Workflows Using Systems Thinking

Sam led three co-design sessions.

Field teams, HQ teams, ministry liaisons, and tech leads built:

- a shared vision

- a unified workflow library

- a modular approval framework

- country-specific adaptations

- a tiered offline strategy

- escalation paths grounded in reality

The CEO attended one session.

She left in tears.

“I didn’t understand how invisible our assumptions were,” she said.

10. Beacon Reborn

Four months later, the re-designed system launched — quietly — in Uganda.

This time:

- workflows were correct

- approvals made sense

- offline mode worked

- SMS integration functioned

- translations landed properly

- caseworkers were trained in local languages

- ministries validated processes

- feedback loops worked

Sam visited the field office in Gulu the week after launch.

He watched a caseworker named Moses use the app smoothly.

Moses turned to him and said:

“This finally feels like our system.”

Sam felt tears sting the corners of his eyes.

11. The Aftermath — and the Lesson

Six months later, Beacon expanded to three more countries.

Donors praised GlobalAid’s transparency.

HQ and field relationships healed.

The project became a model for other NGOs.

But what mattered most came from a young programme assistant in Kampala who said:

“When you fixed the system, you also fixed the silence.”

Because that was the real success.

Not the software.

Not the workflows.

Not the training.

But the trust rebuilt at every hand-off.

Reflection: What This Story Teaches

Cross-continental projects don’t fail at the build stage.

They fail at the handoff stage — the fragile space where invisible assumptions collide with real-world constraints.

The Beacon collapse demonstrates three deep truths:

1. Assumptions Are the First Point of Failure

Using Surface and Test Assumptions, the team uncovered:

- structural mismatches

- hidden expectations

- silently diverging realities

Assumptions left untested become landmines.

2. Decision-Making Architecture Shapes Behaviour

Mastering Effective Decision-Making showed that unclear authority:

- slows work

- suppresses honesty

- produces fake alignment

- destroys coherence

3. Systems Thinking Reveals What Linear Plans Hide

Using Systems Thinking exposed feedback loops of:

- overconfidence

- silence

- misalignment

- conflicting incentives

The map explained everything the dashboard couldn’t.

In short:

Projects aren’t undone by complexity

but by the spaces between people

where assumptions go unspoken

and decisions go unseen.

Author’s Note

This story highlights the fragility of cross-team hand-offs — especially in mission-driven organisations where people assume goodwill will overcome structural gaps.

It shows how FailureHackers tools provide the clarity needed to rebuild trust, improve decisions, and design resilient systems.